Health policy

Most people alive today are affected by health policy, meaning that improvements in this area could impact billions of people.1

Health policy is a broadly defined term that is normally understood as the decisions, plans, and actions that are undertaken to achieve specific healthcare goals within a society. At a minimum, this involves a nation's government acting to improve the health of its citizens, but could also include other organisations that influence policy at national and international levels. On this page, we'll keep the scope of health policy very large, including policies affecting medical research, the health workforce, healthcare financing, or regulation of harmful products (such as lead paint or tobacco).

Donors can influence health policy in a variety of ways. Most organisations will focus on at least one of these three categories of health policy work (which often overlap):

- Asks: Working out what policies we should ask to be adopted.

- Influence: Persuading an institution to adopt policies asked for.

- Implementation: Helping institutions take action based on a policy they have adopted.

For example, there is strong evidence that taxing sugary drinks lowers consumption and improves health (helping us know what to "ask" for). Bloomberg Philanthropies Obesity Prevention Program led a campaign in South Africa that engaged policymakers and the public to raise support for increased taxes on sugary drinks (the "influence"). In December 2017, the sugary drinks tax was signed into law and took effect in April 2018 (the "implementation"). While it is difficult to know how much of this policy action is due to the campaign, it is somewhat likely that the campaign had a large impact on the dietary choices and health of millions of South Africans.

This page primarily focuses on public health policy in low- and middle-income countries, as this is where the majority of disease burden is concentrated and where we expect programmes to have the most impact.

Why is health policy important?

Health policy is less neglected than our other high-priority causes, and estimating tractability is challenging. However, we think it is a promising area due to its large scale. We are also optimistic about more evidence-based donation opportunities appearing in the next few years, as GiveWell is investigating programmes in this area.

What is the scale of health policy?

Health policy affects most people alive today, but we expect donors can have the greatest impact by supporting improvement in low- and middle-income countries. This is because such policies affect a very large number of people living with poor health, and historically, there has been little investment in healthcare in these countries.

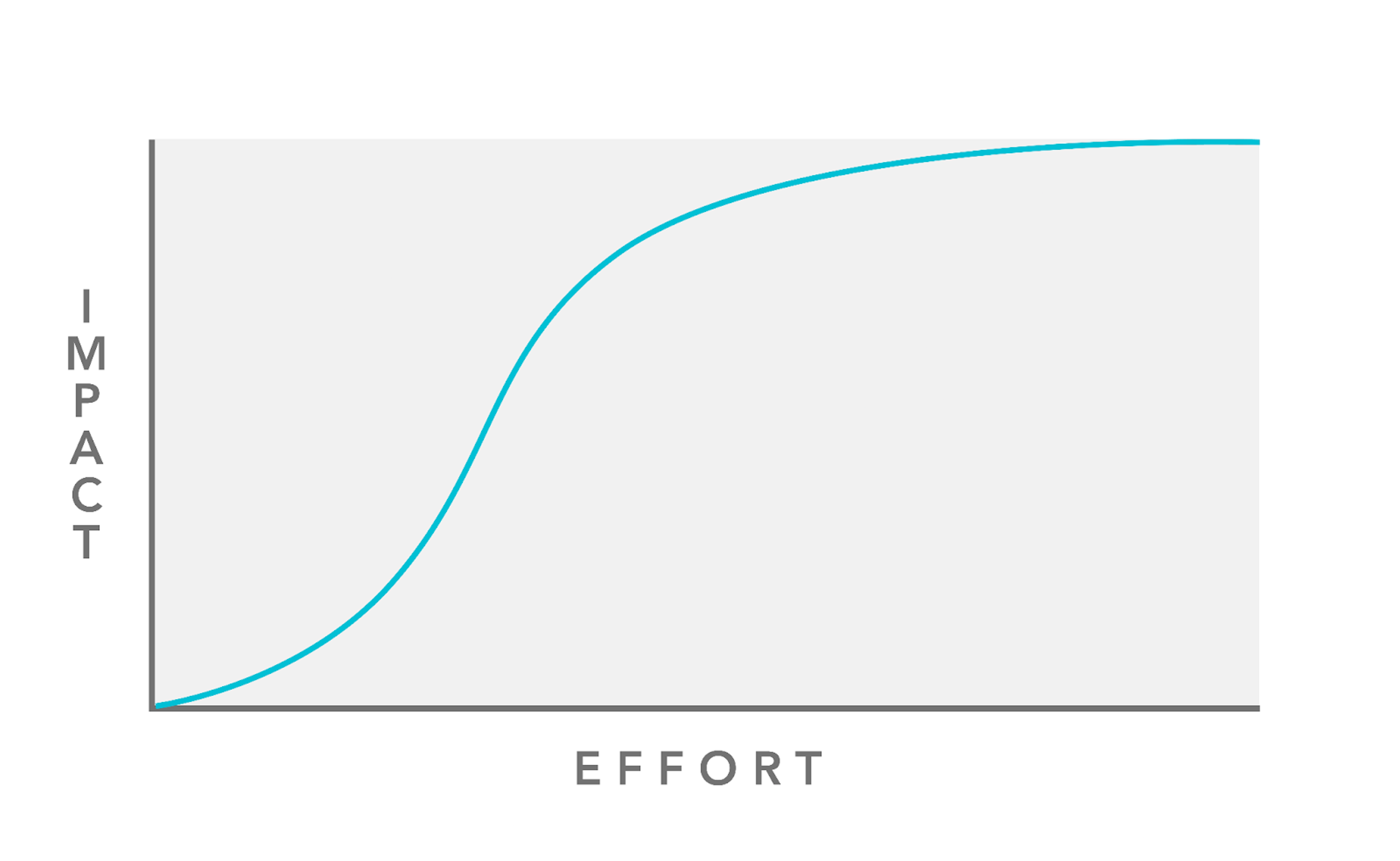

We also expect to see diminishing returns in spending on improving health policy (as shown in the graph below). This means that at some point, every additional dollar spent has a lower marginal impact than the dollar spent before it, until a very large amount of money is required to have any impact at all. Put another way: countries that haven't spent much on healthcare probably have some opportunities to improve health for very little money, such as improving nutrition, sanitation, and basic preventative measures.

Graph showing diminishing returns to effort. In this case, effort is similar to healthcare spending.

Though there are other tools available for improving health outcomes, in some cases policy can have a uniquely large impact.

One reason for this is that some interventions can't be directly implemented by non-governmental organisations — they require changing government policy. For example, one of the most promising interventions in tobacco control is increasing tobacco taxes. This reliably lowers consumption of tobacco products (which cause around 8 million premature deaths per year), while generating revenue for governments that can be spent on other health programmes.

Another reason that advocating for improvements to health policy can have an especially large impact is because policy changes are leveraged. The idea is that changes to policy don't require donors to incur ongoing costs, but instead leverages the effectiveness of resources already being spent. For example, in the case of raising tobacco taxes, the intervention moves resources away from companies selling a harmful product into the hands of governments who are aiming to improve the lives of their citizens. This kind of leverage is somewhat specific to policy work. For example, distributing antimalaria bed nets is extremely cost effective, but it requires a constant stream of funding from donors to sustain.

In sum, policy advocacy has an enormous potential scale for positive impact, though it also has some unique challenges, which we discuss below.

Is health policy neglected?

When considering how neglected a cause is, we look at the total amount of resources going into it. But policies that affect citizens' health can be implemented in a variety of areas — this makes it difficult to get a sense of exactly how many people are working on this issue, and how much money is being spent on improving health outcomes through policy. That said, we can look at a few different ways of assessing the resources allocated to this cause area.

Most governments have a dedicated health ministry (or similar body) that is responsible for improving the health of its citizens. Governments normally dedicate a significant amount of their budget for health spending (on average around 5% of GDP in low- and middle-income countries). Some governments have drastically larger budgets than others, meaning that on average, low- and middle-income countries spent just $264 USD per person on healthcare (compared to $3,631 USD in the UK and $5,355 USD in the US). This discrepancy indicates that there are comparatively more opportunities to make improvements via policy in low- and middle-income countries.

It's difficult to map the territory of non-governmental spending on increasing the efficacy of health policy, but there are a variety of well-known organisations dedicating significant resources to improving health policy, including:

- World Health Organization

- World Bank

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

- Bloomberg Philanthropies

- Center for Global Development

- J-PAL

While these organisations have many different agendas, some of their work is focused on the most promising areas that we are aware of (such as tobacco policy, alcohol policy, and lead paint elimination).

The above list contains foundations worth hundreds of millions of dollars and research groups with Nobel Prize winners, so it seems plausible that this area is much less neglected than other causes aiming to improve the welfare of beings alive today (particularly animal welfare). One area that does seem neglected is finding promising funding opportunities in health policy, an area that GiveWell is moving into.

Is health policy tractable?

As discussed above, organisations aiming to improve health policy first determine what to ask for, influence those in a position to adopt new policies, and then implement those policies.

To determine the total tractability of improving health policy, we need to multiply these values together.

Ask tractability

Some of this research is very tractable, particularly when the policy can be assessed through a randomised control trial. For example, the efficacy of long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets to protect people from malaria has been rigorously studied, so directing government funding towards this intervention is highly tractable.

Other policies are difficult to assess due to issues such as a lack of randomisation, finding control groups, or implementation in multiple contexts. This is particularly true for policies that require many years to see the effects. Like with direct interventions, there will also be a variety of flow-through effects — unanticipated medium- and long-term consequences — which may be positive or negative, and are difficult to measure.

Overall, health policy "ask" research seems to vary in tractability. Some types of research seem less tractable than comparable work on the most evidence-based and cost-effective direct interventions we are aware of.

Influence and implementation tractability

Influencing health policy can be very challenging for non-governmental organisations. There can be a lot of bureaucracy to navigate, and it's often critical to have knowledge of governmental systems (which have varying degrees of transparency) as well as connections to key decision-makers. Many of the best health policies can be implemented through health ministries, which have clear objectives to improve health outcomes and so are interested in policies that can achieve that. But it can be challenging when coordinating with other parts of government with more complex objectives.

As running a policy intervention is very costly and context specific, it can be difficult for organisations to build a track record of changing policies. These interventions are often "hit or miss" — the organisations will either have a very large impact if the policy is implemented, or almost no impact if it isn't.

Another issue is that it can be very difficult to tell if the work done to influence a policy is having success. For example, an organisation aiming to increase tobacco taxes might have no idea if they will be successful up until the minute before the taxes are increased (or not). And even if a policy is passed, it is difficult to know how much of the impact is attributable to a single organisation (particularly when there are many organisations advocating for a similar issue).

Governments may also implement the policy poorly, leading to less impact than expected. To address this, some organisations provide technical assistance to governments implementing a policy to ensure that the policy is as impactful as possible.

Overall tractability

Overall, health policy seems somewhat tractable. While there are examples of organisations that have implemented effective health policies, there is a lot of uncertainty about which organisations are able to reliably influence policy and ensure policies are implemented effectively, and which policies are the most effective.

What are the potential solutions to improving health policy?

GiveWell is exploring a range of interventions that look particularly promising in improving health policy. The areas that they are most interested in are listed below.

Public health regulation

Some regulations to improve public health have had a large impact in high-income countries. Low-income countries may lack the capacity or political will to implement these regulations, so charities can provide technical assistance to accelerate regulation or improve implementation.

Some promising interventions in this area include tobacco and alcohol control, lead paint regulation, road safety, micronutrient fortification, and pesticide regulation (to decrease suicides due to pesticide ingestion).

Improving government programme selection and implementation

Low-income countries may not have the resources to select good programmes or implement programmes effectively. Charities can assist governments in effectively implementing their programmes, or help governments choose which programmes to prioritise.

Organisations working in this area include Innovation in Government Initiative, Innovations for Poverty Action, IDinsight, and Deworm the World Initiative.

Improving or increasing aid spending (or spending on cost-effective direct programmes)

A large proportion of aid from high-income countries is spent on global health and development. Non-governmental organisations can provide technical assistance helping governments spend their money effectively, as well as advocating for more aid spending from high-income countries. Government funds account for a significant amount of spending on aid and while GiveWell is focused on delivering money to highly cost-effective interventions, governments could also increase the proportion of their aid spending on cost-effective programmes.

Organisations working in this area include the Center for Global Development, ONE Campaign, and the Overseas Development Institute.

Reducing the cost of health commodities

Lower costs of medical commodities can improve healthcare coverage and economic wellbeing for low-income households.

One organisation working in this area is the Clinton Health Access Initiative.

Why might you not prioritise health policy?

Other interventions are supported by more evidence

While there are many evidence-based policies that could be implemented, many institutions influencing health policy have a lower bar for empirical evidence than the best charities recommended by GiveWell. This is likely partly due to governments placing less importance on empirical evidence (relative to GiveWell), and partly due to many interventions being difficult to assess empirically.

In addition to this, unlike charities that run direct interventions (the type reviewed by GiveWell) there is often little empirical evidence for an organisation's effectiveness. Changing policy can take a long time, and there are few reliable signals for making progress on a policy change — you only see an impact if the policy change is achieved, and even then it's difficult to attribute the impact to a specific organisation. This means that health policy initiatives could have a large expected impact but often achieve negligible actual impact, and it may even be difficult to know if the expected impact should be large to begin with.

You think other policies are more important

You may think policy interventions are important, but be uninterested in health policy. This could be because you are worried about the potential harms of poorly implemented health policy, or you think there are more promising opportunities. For example, you may think that increasing the rate of economic growth would be more beneficial for health outcomes than health policy.

You may have other priorities

Finally, you may prioritise other giving opportunities, such as improving economic conditions, improving the lives of other sentient beings (such as factory farmed animals), or focusing on future generations.

What are the best health policy charities, organisations, and funds?

You can donate to several promising programs working in this area via our donation platform. For our charity and fund recommendations, see our best charities page.

Learn more

- Evidence Based Policy Executive Summary (Founders Pledge)

- History of Philanthropy Case Study: The Founding of the Center for Global Development (Open Philanthropy)

- How GiveWell's research is evolving (GiveWell)

- Growth and the case against randomista development (Hauke Hillebrandt and John Halstead)

- 'Best Buys' and other Recommended Interventions for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases (World Health Organization)

Our research

This page was written by Caleb Parikh. You can read our research notes to learn more about the work that went into this page.

Your feedback

Please help us improve our work — let us know what you thought of this page and suggest improvements using our content feedback form.