Mental Health interventions may be more cost-effective than we think

Neither Giving What We Can nor GiveWell currently feature a single mental health-focused organisation in their recommendations, despite mental disorders accounting for over one-fifth of all days lived with disability worldwide.

A recently released report by the Center for Global Development suggests that mental health interventions in low and middle income countries (LMIC) may be more cost-effective than previously assumed. As currently favoured interventions reach diminishing marginal returns, mental health may rapidly become an interesting field for effective donations, although some significant concerns remain about tractability.

The global mental health burden of disease

Mental, neurological and substance use disorders (MNS) account for an estimated 7.4% of the global disease burden[1]. This realisation is at the foundation of a recent report penned by Victoria de Menil on behalf of the Centre for Global Development. De Menil’s report lays out the scale of the mental health problem, estimated to affect 700 million people globally[2], and makes three specific policy recommendations:

- scaling up universal health coverage,

- creating incentives through results-based funding,

- implementing conditional cash transfers.

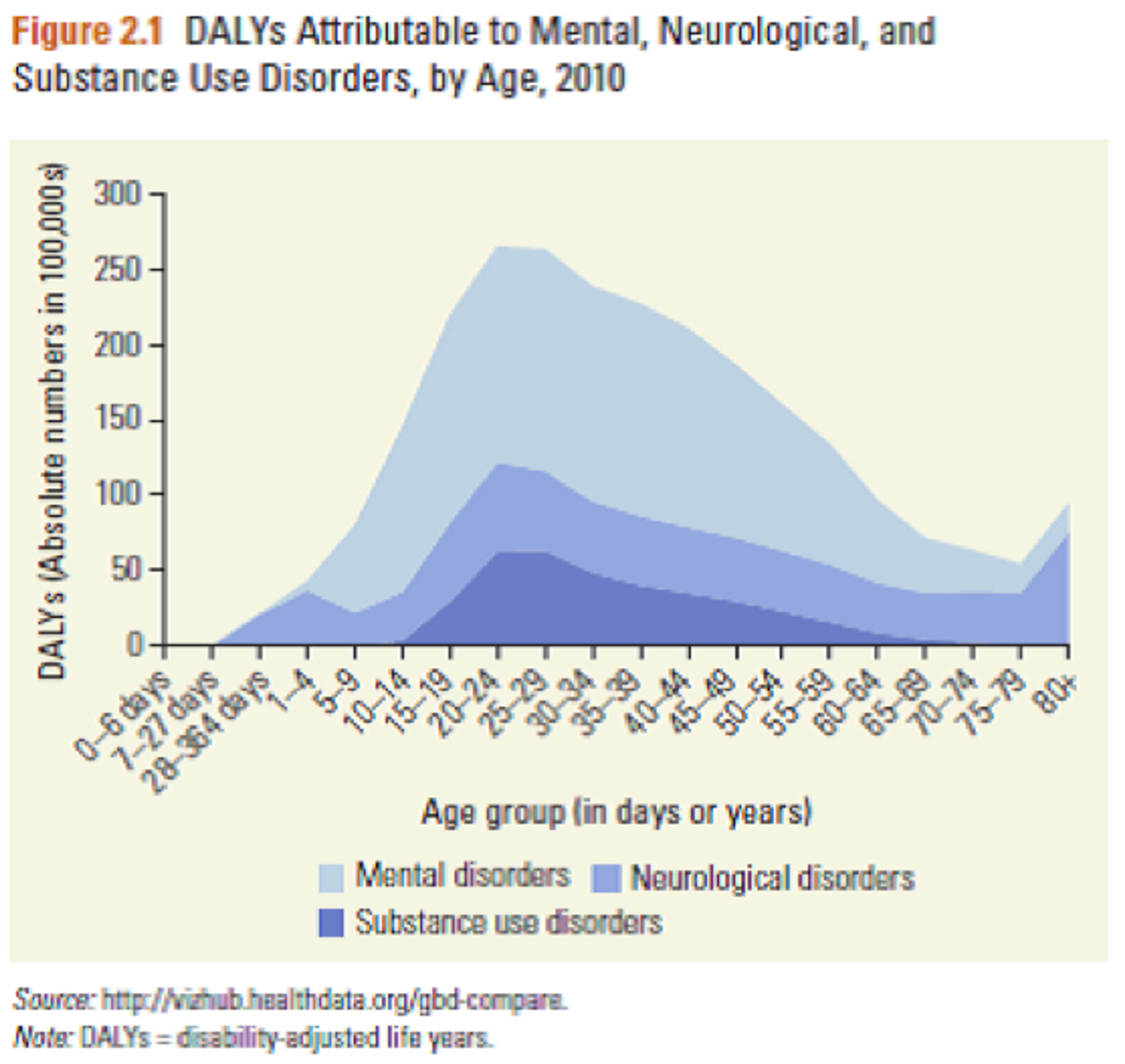

MNS disorders are one of the top five contributors to the global burden of disease [1], and are responsible for 37% of the total disease burden from non-communicable diseases[3]. Moreover, they carry a high death toll through suicides and contributing to premature mortality in various ways.

Importantly, the problem posed by mental disorders is actually getting worse: disease burden as measured in DALYs increased by 38% between 1990 and 2010[1], and is expected to continue on this trajectory as populations age and demographics shift (since MNS disorders, especially neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s, disproportionately affect adults).

Finally, mental disorders are cause for some of the most serious human rights abuses committed in LMIC, both within families and communities (sexual abuse, forced restraint) and by governments (forced sterilization or incarceration).

Mental health disorders are also directly related to poverty. Stress and emotional anxiety experienced in relation with poverty may trigger mental disorders (the ‘social causation’ hypothesis). Conversely, crippling healthcare costs and frequent unemployment associated with mental health problems may serve to drive individuals into poverty or keep them there (the ‘social drift’ hypothesis).

Despite a substantial literature on effective interventions, mental health is starkly neglected by LMIC governments. According to de Menil, “one third of LMIC do not have a designated budget for mental health… and among those that do, the average expenditure on mental health in low-income countries is 0.5% of the total health budget.” She contrasts the treatment gap in Nigeria – 90% across all diagnosable mental disorders – with an average of 32% for schizophrenia to 56-57% for depression and anxiety disorders in European countries.

Remarkably, the international donor community fares no better: only 0.7% of development spending is directed at mental health [4] (despite a disease burden of over ten times this scale relative to the global total). A significant obstacle here is the lack of reliable data on MNS disorder prevalence in many LMIC.

Are MNS interventions cost-effective?

De Menil is adamant that the problem lies in implementation – especially at the institutional level – not in generating effective interventions: Cost-effective, proven and scalable interventions, she claims, are readily available, focusing on three examples (universal health coverage, results-based funding, cash transfers).

Importantly, de Menil’s main source of data for her cost-effectiveness estimates, the Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries (DCP2) report (2006), is almost ten years old, calling for significant caution on any inferences made from these figures. (Disclaimer: GiveWell has further offered strong criticism of some aspects of the DCP2 report.)

To investigate cost-effectiveness, the DCP2 authors modelled the aggregate effects of a bundle of the most effective treatment options across four disorder archetypes (schizophrenia and related non-affective psychoses, bipolar affective disorder, major depressive disorder, panic disorder).

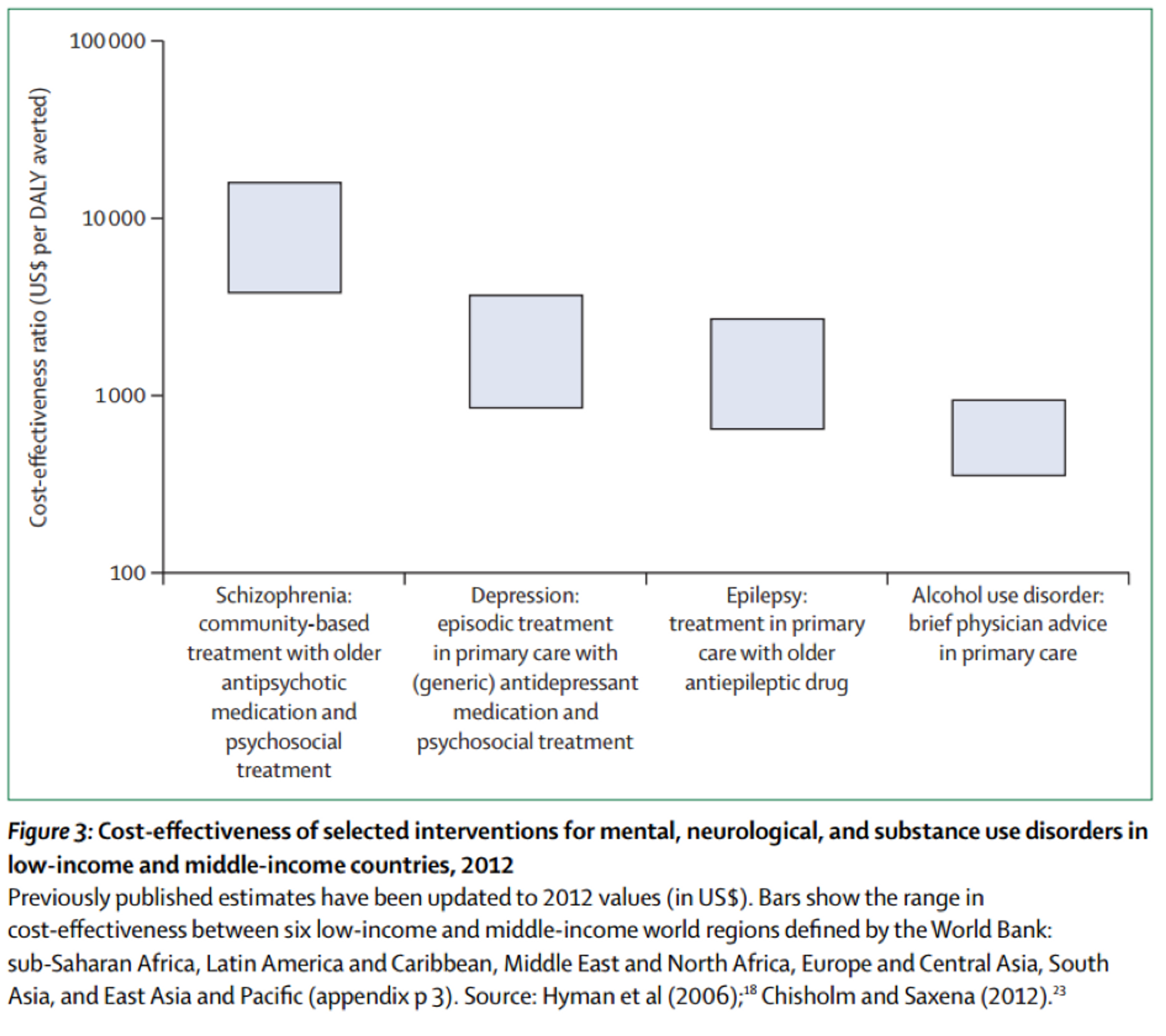

Their analysis suggests that mental health interventions work out at $1,000-$2,000/DALY averted in Sub-Saharan Africa and $2,300-$4,500/DALY averted in Latin America and the Caribbean. (For comparison, GiveWell currently estimates the effectiveness of distributing anti-malarial bed nets at approximately $100/DALY averted.)

Since these figures represent average values across a bundle of interventions, targeting only the most effective disease incidences could prove significantly more cost-effective. De Menil mentions “a wide range [of effectiveness] across disorders and populations; brief interventions for harmful alcohol use and treatment of epilepsy with first-line anti-epileptic medicines fall towards the lower (more favorable) end, while community-based treatment of schizophrenia with first-generation medication and psychosocial care falls towards the upper end.”

An updated version of the DCP2 report (DCP3), released in October 2015, reaches even more optimistic conclusions. Surveying studies on cost-effectiveness published between 2007-2012, they find broadly the same estimates while complementing the lower end of the scale with alcohol-demand reduction measures, projected at approximately $200-$1,200/DALY averted[5]. One can therefore treat $1,000-$2,000/DALY averted as a conservative estimate of the cost-effectiveness of the best mental health interventions.

Is mental health a tractable problem?

Stigma represents a – if not the – key obstacle to effective treatment of mental health disorders. In a number of LMIC “there has been a discourse that mental health problems don’t exist.” [6] Families resort to forcible restraint out of helplessness how to deal with affected relatives. Fear of contagion of mental illness results in patients being denied physical touch or ostracised by their communities[7].

Additionally, ignorance of the neuropsychiatric causes of mental health disorders may drive communities to rely on ineffective practices such as “faith-healing rituals” or “nontherapeutic herbal supplements” (de Menil). Interventions aimed at combatting stigma are likely much harder to implement than direct-treatment interventions – pursuing change on a systemic scale may prove prohibitively costly or uncertain.

A second obstacle may affect the scalability of mental health interventions. In surveying successful examples of mental health policy reforms in four countries (India, China, Ethiopia, South Africa), de Menil repeatedly points out national and regional idiosyncrasies that may complicate transferring proven interventions from one context to another. In particular, different communities place varying degrees of emphasis on home vs. institutional care, “paraprofessionals” (traditional healers, village authorities) vs. specialist workers, recovery vs. symptom management, and openness to learning from external partners.

Which organisations currently operate in this area?

The mental health charity space is not crowded. The Center for Global Mental Health lists only eight NGOs active in this field. Of those, only three are not limited to a specific country or region.

BasicNeeds appears to be the sole large charity active in reducing the global mental health disease burden. It provides “medication and psychosocial support in partnership with local governments and Ministries of Health … [, builds] the capacity of existing health professionals and services … [and] participants by encouraging them to be members of self-help groups … [and] create[s] livelihood opportunities for people with mental illness and epilepsy.”

Initial cost-effectiveness estimates of BasicNeeds’ Mental Health and Development programs support the hypothesis postulated above that targeting individual disease may prove even more effective than the DCP2 figures: de Menil et al. place the incremental cost over two years per DALY averted at $727. (For full disclosure it should be added that de Menil was employed by BasicNeeds between 2007-2010.) BasicNeeds claims to have helped “over 646,000 people in 12 countries.”

Is mental health a promising area for Effective Altruism?

Mental health interventions are important considering their neglectedness and the scale of the disease burden. The political nature of stigma-related obstacles to change provide some problems for tractability, but local interventions circumventing these problems are conceivable; de Menil’s policy recommendations may provide promising starting points for developing more effective interventions.

It seems that mental health interventions may not be among the most effective right now, but given their comparative cost-effectiveness, may rank high in succession when the best current programs approach diminishing marginal returns.

What actions can I take?

You could give to one of the charities currently working on improving mental health in LMIC. The most plausible candidate appears to be BasicNeeds, although limited available data means there is significant uncertainty about the effectiveness of their programs. Before doing this, you might want to read about Giving What We Can’s recommended charities.

You could pursue or fund further research into what are the most effective interventions in the mental health sphere. A lack of data (e.g. on treatment gaps or the effectiveness of existing interventions) and of highly effective policy recommendations reflect major room for further study of this area. Mental health disease burden alleviation currently seems neglected, and as some other effective charities approach funding saturation, there will be demand for new opportunities to direct funding.

You could also consider setting up an effective mental health charity yourself. The scale of the problem is significant in LMIC, and the same considerations about neglectedness listed above apply here. The upcoming DCP3 report is likely a good starting point for which disorders allow for the most effective interventions. Advice on setting up your own effective charity can be found here.

References

- Whiteford, Degenhardt et al. (2013), as cited in Victoria de Menil. 2015. "Missed Opportunities in Global Health: Identifying New Strategies to Improve Mental Health in LMICs." CGD Policy Paper 068. Washington DC: Center for Global Development.

- Patel and Saxena (2014), as cited in de Menil

- Bloom, Cafiero et al. (2011), as cited in de Menil

- Gilbert, Patel et al. (2015), as cited in de Menil.

- Vikram Patel et al. (2015). “Addressing the Burden of Mental, Neurological, and Substance Use Disorders: Key Messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd Edition.” The Lancet.

- Summerfield (2013), as cited in de Menil.

- Human Rights Watch (2012), as cited in de Menil.